On 16th November 2017, China’s Ministry of Land and Resources announced that natural gas hydrates were officially approved as a new mineral by the State Council, becoming the 173rd mineral in China. The term “natural gas hydrate” may seem both familiar and mysterious. Excitingly, China’s first offshore trial production of natural gas hydrates set world records for both production duration and total output. Today, let’s follow Xiao Y to explore how these tiny crystalline compounds pack such immense energy!

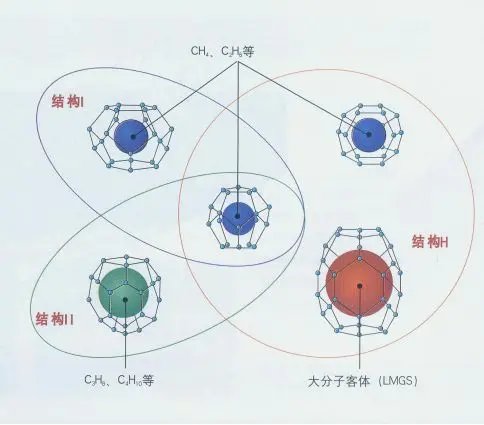

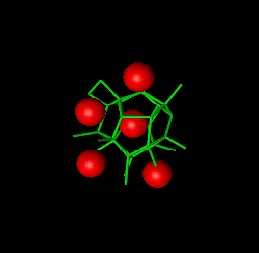

Natural gas hydrates are crystalline compounds in which methane molecules are trapped within a lattice of water molecules under low temperature and high pressure. They are commonly referred to as “flammable ice”.

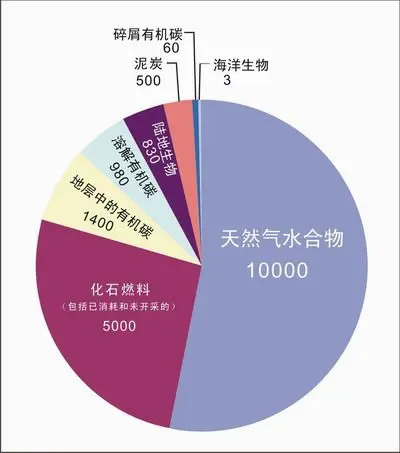

Natural gas hydrates occur primarily in permanently frozen permafrost regions around the Arctic and in shallow marine sediments on continental shelves. Submarine hydrate resources contain orders of magnitude more methane than estimated conventional natural gas reserves. According to the US Geological Survey, global natural gas hydrates contain approximately 20,000 trillion cubic metres of methane.

Compared to other fossil fuels, natural gas hydrates are a potentially enormous energy resource. The US Department of Energy estimates that the United States alone holds 2,830–8,490 trillion cubic metres. Even if only 1–2% of global hydrates are economically recoverable, they still represent a massive energy reserve.

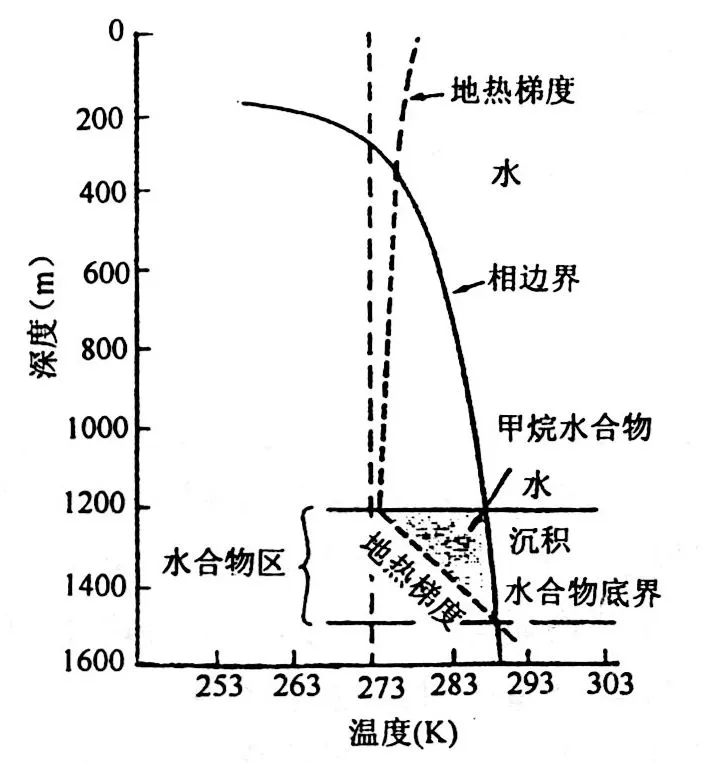

Four fundamental conditions are required for hydrate formation:

① Low temperature, generally below 10°C;

② High pressure, typically exceeding 10 MPa;

③ A source of natural gas, including deep thermogenic gas and shallow microbial biogas;

④ A favourable reservoir space to accommodate the hydrate.

Extraction techniques include thermal stimulation, depressurisation, chemical injection, and CO₂ replacement methods.

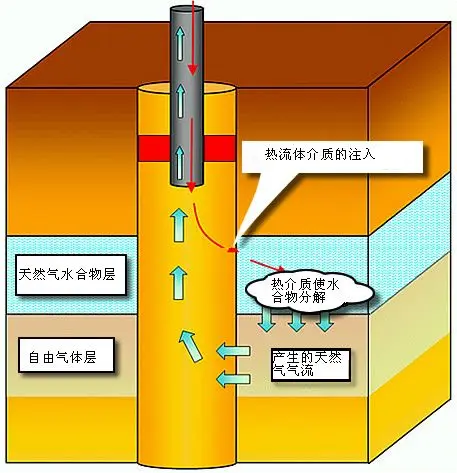

Thermal Stimulation

Thermal stimulation involves injecting hot water under constant pressure, raising the system temperature to the decomposition threshold. This approach is costly and requires simultaneous downward heating and upward gas production.

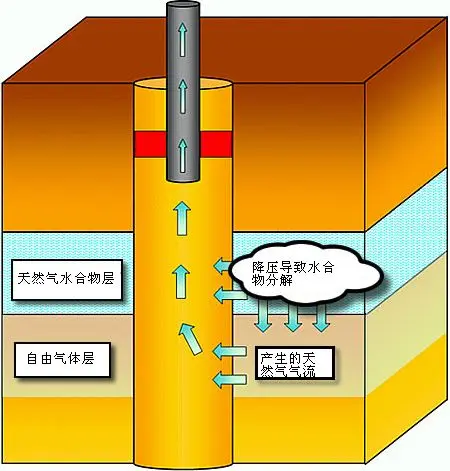

Depressurisation

Depressurisation extracts hydrates by lowering the pressure in the gas layer adjacent to or within the hydrate-bearing sediments.

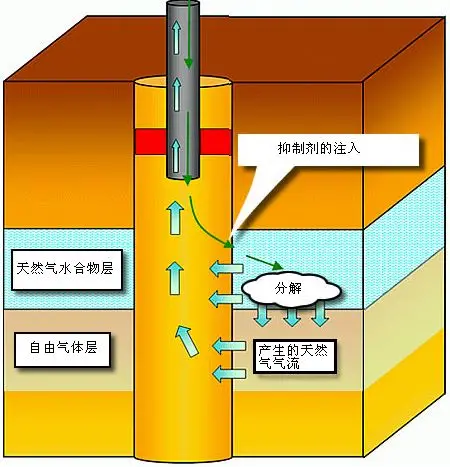

Chemical Injection

Chemical injection involves adding substances like methanol to alter the temperature-pressure equilibrium, causing hydrates to destabilise and decompose in situ.

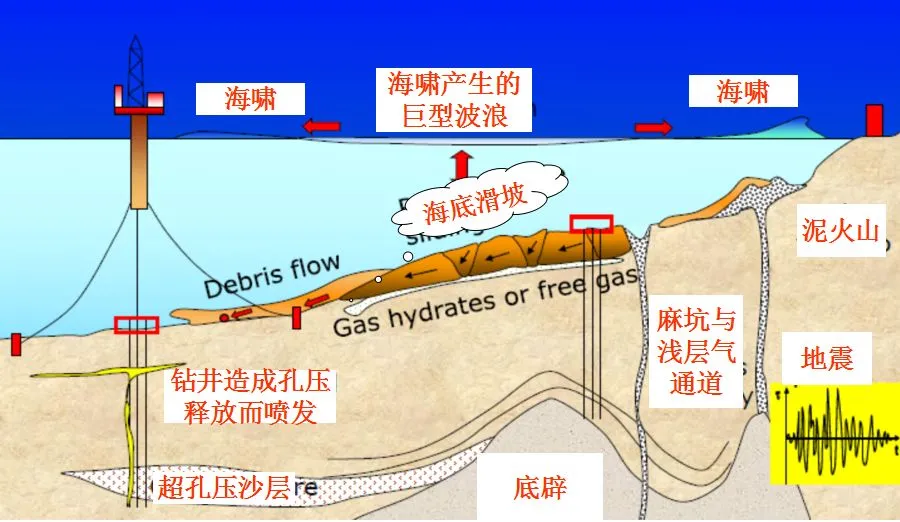

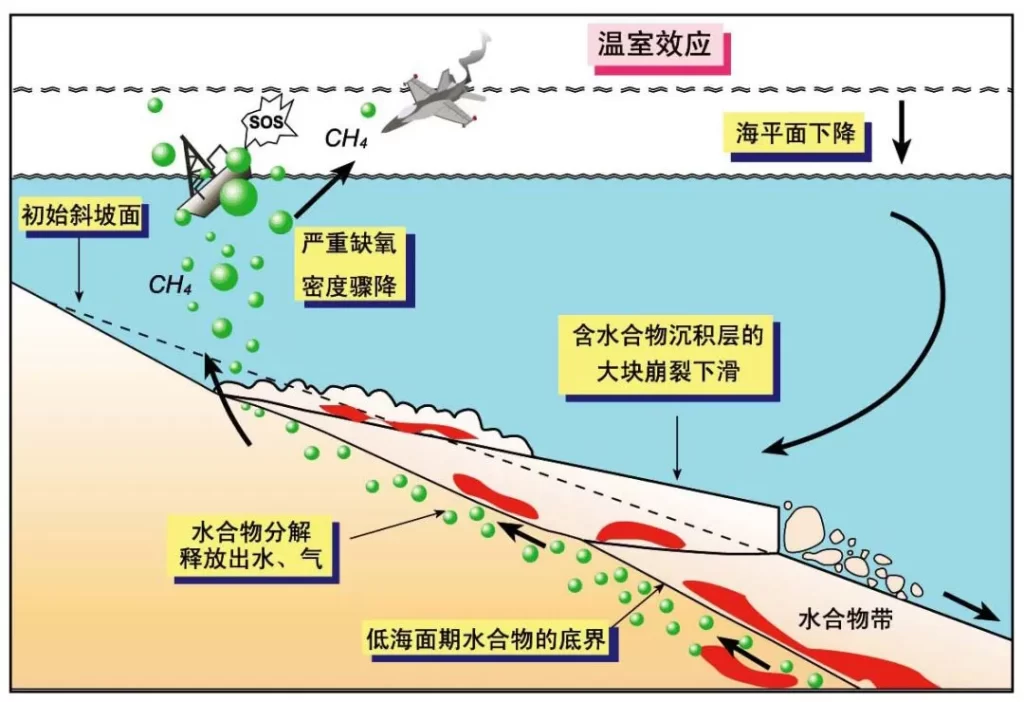

Extraction reduces the consolidation of hydrate-bearing sediments and releases gas, generating overpressure. Gravity loading or seismic disturbances can trigger sediment collapse and submarine landslides.

Specifically, hydrate extraction may trigger four types of geological hazards:

Pipeline blockage: obstructing oil and gas transport

Submarine landslides: causing tsunamis and threatening subsea cables and engineering structures

Global warming: greenhouse gas release, primarily methane and CO₂

Biodiversity loss: mass extinctions, historically including dinosaurs

Although natural gas hydrates offer tremendous potential, they also carry significant risks. Estimates suggest global submarine methane reserves are roughly 3,000 times greater than the methane in Earth’s atmosphere. Uncontrolled releases during extraction could exacerbate greenhouse effects. Safely and economically extracting hydrates while efficiently recovering methane remains a key challenge for nations worldwide.

Laboratory synthesis of hydrates has become a popular research focus in recent years, demanding significant investment. The critical challenge is accurately measuring both the quantity and distribution of hydrates, an area where low-field NMR excels. However, in methane hydrate studies, hydrogen signals arise from both methane and water, and changes in temperature and pressure affect not only hydrate formation but also NMR detection. Consequently, continued investment in human and material resources is needed to overcome these technical challenges in the field.

Phone: 400-060-3233

After-sales: 400-060-3233

Back to Top