Starch, as the primary carbohydrate source in the human diet, has a digestion rate closely linked to postprandial blood glucose levels. Natural starches can be classified by crystal type into A-type (e.g., wheat starch), B-type (e.g., potato starch), and C-type (e.g., pea starch), each exhibiting significantly different digestibility. With the rising prevalence of metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, the development of low glycaemic index (GI) foods has become a pressing need.

Research indicates that proteins and their hydrolysates can inhibit starch digestion through physical encapsulation or molecular interactions. Soy protein isolate hydrolysates (SPIH), with their low molecular weight, high solubility, and abundant functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, amino), may form stronger interactions with starch. However, existing studies lack a systematic analysis of the differential response of various starch crystal types, and the interaction mechanisms between SPIH and starch—such as hydrogen bonding and water modulation—remain unclear.

In this study, low-field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (LF-NMR) was primarily used to analyse the effects of SPIH on water mobility and distribution in different starch crystal types, revealing the interaction mechanisms and the physical basis for its anti-digestibility.

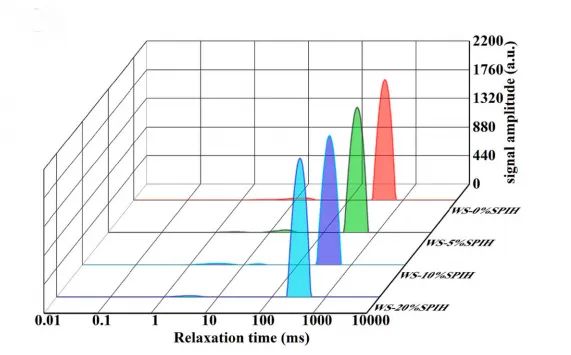

Figure 1: Relaxation spectra of wheat starch with SPIH

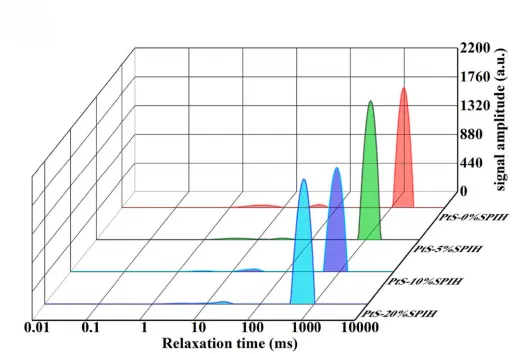

Figure 2: Relaxation spectra of potato starch with SPIH

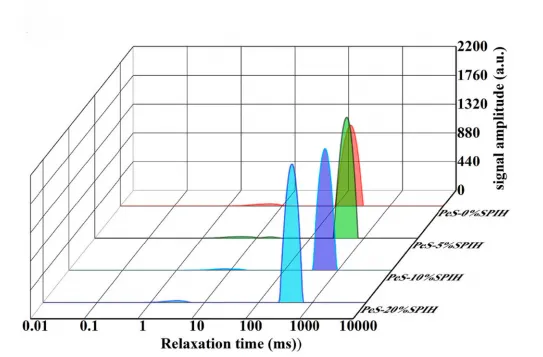

Figure 3: Relaxation spectra of pea starch with SPIH

1. Classification of Water States by Relaxation Time

LF-NMR divides water in starch systems into three categories based on T2 relaxation:

1. T21 (0.1–10 ms): Bound water tightly associated with starch/protein functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl), exhibiting very low mobility;

2. T22 (10–100 ms): Immobilised water constrained by starch gel networks or protein structures, with limited mobility;

3. T23 (100–1000 ms): Free water residing in starch intergranular spaces or gel pores, highly mobile and closely related to starch digestibility.

Without SPIH: The T23 peak is centred around 440 ms, corresponding to approximately 76% free water (A23 amplitude).

After adding 20% SPIH:

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

A23 amplitude drops to 59%, and immobilised water T22 amplitude rises from 15% to 27%.

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

T23 peak shifts left to ~460 ms, shortening relaxation time by 47.7%.

A23 amplitude drops to 59%, and immobilised water T22 amplitude rises from 15% to 27%.

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 peak shifts left to ~460 ms, shortening relaxation time by 47.7%.

A23 amplitude drops to 59%, and immobilised water T22 amplitude rises from 15% to 27%.

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 880 ms, free water fraction 81% (A23).

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 peak shifts left to ~460 ms, shortening relaxation time by 47.7%.

A23 amplitude drops to 59%, and immobilised water T22 amplitude rises from 15% to 27%.

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 880 ms, free water fraction 81% (A23).

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 peak shifts left to ~460 ms, shortening relaxation time by 47.7%.

A23 amplitude drops to 59%, and immobilised water T22 amplitude rises from 15% to 27%.

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Mechanism: Amino groups in SPIH form hydrogen bonds with starch hydroxyls, converting free water into bound water and reducing water availability for starch granule swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 880 ms, free water fraction 81% (A23).

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 peak shifts left to ~460 ms, shortening relaxation time by 47.7%.

A23 amplitude drops to 59%, and immobilised water T22 amplitude rises from 15% to 27%.

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

The A23 amplitude decreases to 68%, while bound water T21 amplitude rises from 12% to 18%.

Mechanism: Amino groups in SPIH form hydrogen bonds with starch hydroxyls, converting free water into bound water and reducing water availability for starch granule swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 880 ms, free water fraction 81% (A23).

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 peak shifts left to ~460 ms, shortening relaxation time by 47.7%.

A23 amplitude drops to 59%, and immobilised water T22 amplitude rises from 15% to 27%.

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

The T23 peak shifts left to about 340 ms, reducing free water relaxation time by 11.4%.

The A23 amplitude decreases to 68%, while bound water T21 amplitude rises from 12% to 18%.

Mechanism: Amino groups in SPIH form hydrogen bonds with starch hydroxyls, converting free water into bound water and reducing water availability for starch granule swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 880 ms, free water fraction 81% (A23).

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 peak shifts left to ~460 ms, shortening relaxation time by 47.7%.

A23 amplitude drops to 59%, and immobilised water T22 amplitude rises from 15% to 27%.

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

The T23 peak shifts left to about 340 ms, reducing free water relaxation time by 11.4%.

The A23 amplitude decreases to 68%, while bound water T21 amplitude rises from 12% to 18%.

Mechanism: Amino groups in SPIH form hydrogen bonds with starch hydroxyls, converting free water into bound water and reducing water availability for starch granule swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 880 ms, free water fraction 81% (A23).

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 peak shifts left to ~460 ms, shortening relaxation time by 47.7%.

A23 amplitude drops to 59%, and immobilised water T22 amplitude rises from 15% to 27%.

Mechanism: The loose B-type crystal structure allows SPIH to penetrate granule pores, physically entangle, and form hydrogen bonds, fixing free water and inhibiting starch swelling.

Without SPIH: T23 peak around 440 ms, free water fraction 72% (A23).

After adding 5% SPIH:

T23 briefly shifts right to ~480 ms, slightly increasing free water mobility, likely due to initial disruption of the starch-water network by SPIH.

After adding 20% SPIH:

T23 shifts left to ~380 ms, free water fraction decreases to 65%, and bound water amplitude rises from 15% to 20%.

Mechanism: The A+B hybrid structure of C-type starch causes a concentration-dependent effect of SPIH; at higher concentrations, SPIH forms stable hydrogen-bond networks with amylose, restricting water mobility.

Reduced free water mobility inhibits starch digestion: SPIH competes for hydrogen bonding and physically encapsulates water, decreasing free water content and delaying granule swelling and exposure of enzymatic cleavage sites.

Water distribution and crystal type sensitivity: B-type starch (potato) is most sensitive to SPIH due to its loose structure allowing deeper SPIH penetration, whereas A-type starch (wheat) has compact crystals, limiting SPIH to surface interactions, resulting in smaller changes in water mobility.

LF-NMR data demonstrate that SPIH forms hydrogen bonds and physical networks with different starch crystal types, reducing free water content and mobility, thereby inhibiting starch digestion. This technology provides dynamic evidence for the “protein hydrolysate–starch–water” interaction mechanism, supporting SPIH’s potential as a low-GI food additive.

If you are interested in this application, please contact: 15618820062

Zhu, Z., Sun, C., Wang, C., Mei, L., He, Z., Mustafa, S., Du, X., & Chen, X. (2024). The anti-digestibility mechanism of soy protein isolate hydrolysate on natural starches with different crystal types. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 255, 128213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128213

Phone: 400-060-3233

After-sales: 400-060-3233

Back to Top