1. Background:

The gas–water flow capacity significantly affects the productivity of coalbed methane wells. Two-phase gas–water flow occurs throughout various stages of coalbed methane development, and spontaneous imbibition is a phenomenon commonly observed in all hydrophilic coal reservoirs. However, research on how spontaneous imbibition damages reservoir permeability and the factors influencing this effect remains limited and lacks definitive conclusions.

Spontaneous imbibition can both enhance gas desorption from coal, which benefits reservoir development, and increase water saturation in the reservoir, which significantly reduces gas-phase permeability, representing a disadvantage. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the imbibition behaviour of coal and its impact on permeability.

2. Sample Characteristics:

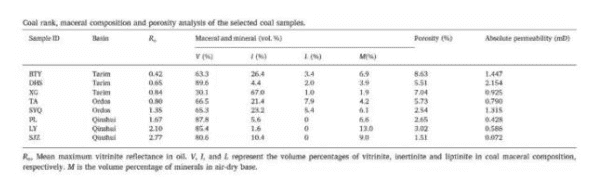

Samples for the imbibition experiments were collected from three basins: Qinshui, Ordos, and Tarim, covering coals ranging from low-rank to high-rank. Basic parameters of the samples are listed in the table below:

During coring, every effort was made to minimise disruption to the core’s original wettability. Core dimensions were approximately 50 mm in length and 25 mm in diameter, facilitating NMR measurements. The outer surface of each core was polished with sand to prevent gas from bypassing along the core edges during displacement experiments.

3. Experimental Methods and Apparatus:

The overall experimental procedure comprised four stages: preparation, wettability evaluation, spontaneous imbibition experiments, and gas-displacement permeability measurements.

01. Spontaneous Imbibition Experiment

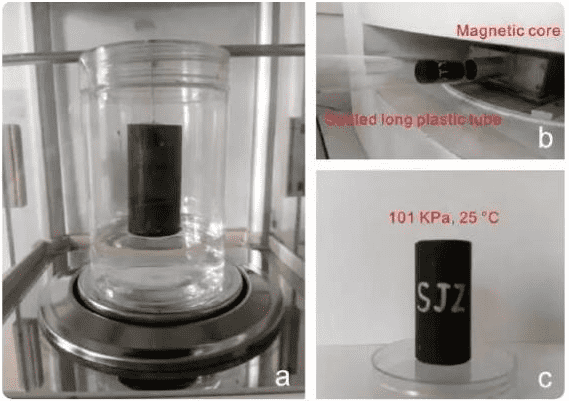

Samples were first dried in an oven at 105 °C for 24 hours. Fully dried samples were initially measured using NMR to obtain baseline signals. For the imbibition experiment, cores were suspended by fine threads in a sealed container containing deionised water. The height of the threads was adjusted so that the base of the coal just contacted the water surface, allowing water to imbibe upward from the core base (co-current imbibition), as illustrated in Figure 1.

During NMR measurements, cores were placed in long-necked glass tubes to prevent water evaporation caused by coil heating. Experiments were conducted at room temperature (~26 °C). The volume of water spontaneously imbibed by the coal was quantified using NMR T2 spectra. Because imbibition initially proceeds rapidly then slows, measurements were taken every 10 minutes in the early stage and every 2 hours in the later stage.

Figure 1: Spontaneous Imbibition and Gas-Displacement Test of Coal Cores

02. Gas Displacement Experiment

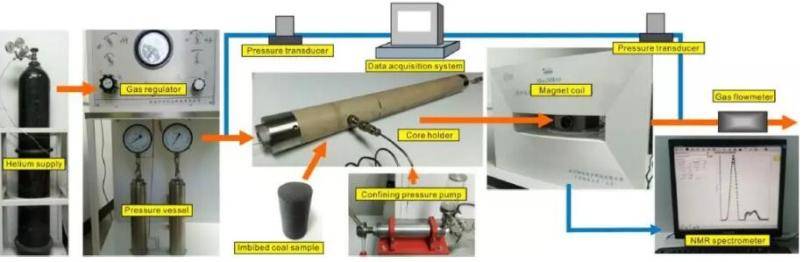

To assess the impact of imbibed water on gas flow capacity, gas displacement experiments were conducted using helium, a non-adsorbing gas that does not alter pore size via adsorption. To simulate in-situ conditions, a confining pressure of 2.8 MPa was applied to low-rank coals and 3.2 MPa to high-rank coals, estimated from sampling depths. The apparatus (Figure 2) consists of a core displacement device, NMR measurement system, and data acquisition unit. NMR measurements were performed using a Meso23-060H-I mid-size NMR imaging analyser from Niumai Analytic.

Figure 2: NMR Gas–Water Analysis System Setup

4. Experimental Results and Discussion:

01. NMR Spectral Features during Imbibition

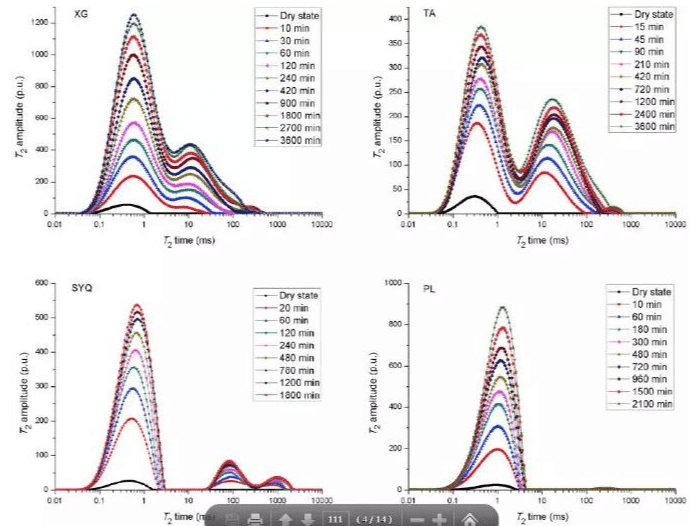

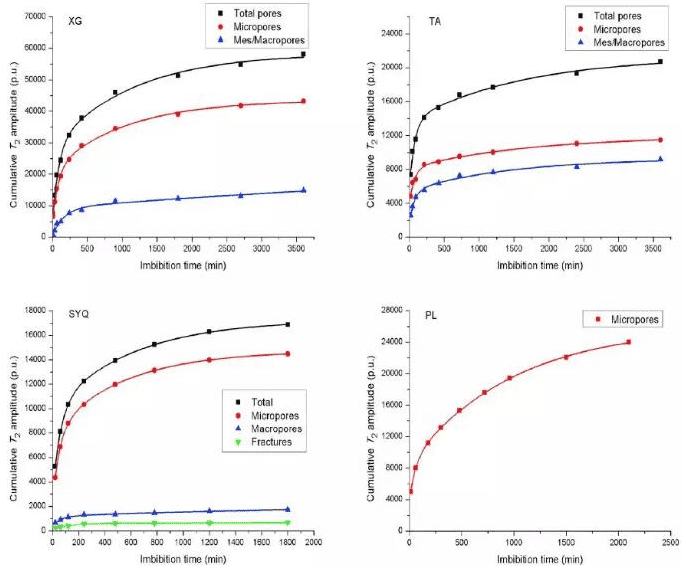

As shown in Figure 3, low-rank coals display two distinct spectral peaks. The left peak (0.1–1 ms) represents surface relaxation in small pores, while the right peak (5–100 ms) originates from surface relaxation in medium-to-large pores, indicating good pore connectivity. High-rank coal samples generally exhibit only a small-pore peak (0.1–1 ms). For high-rank sample SYQ, a second minor peak appears at T2 > 100 ms, disconnected from the small-pore peak, corresponding to water in microfractures. During imbibition, signal intensities from various pore sizes increase over time, but at different rates (Figure 4).

Figure 3: NMR Spectral Evolution during Spontaneous Imbibition

Figure 4: Imbibed Water Volumes in Different Pore Types

02. Influence of Coal Rank on Imbibition

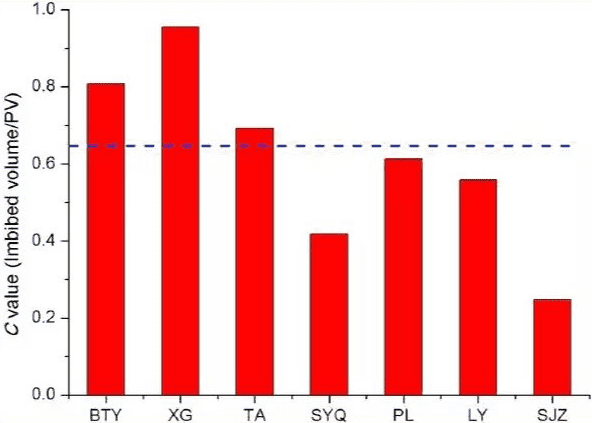

The imbibition capacity C-value quantifies the effect of coal rank on spontaneous imbibition. It represents the ratio of the imbibed volume (Zda) to total pore volume. Figure 5 shows C-value distributions for various samples: low-rank coals have an average C = 0.81, high-rank coals average C = 0.46. This indicates low-rank coals exhibit stronger imbibition, with roughly 80% of pores water-filled at equilibrium. A C-value of ~0.65 can serve as a boundary between low- and high-rank coals in imbibition tests.

Figure 5: Distribution of Imbibition Capacity (C) across Samples

03. Influence of Wettability on Imbibition

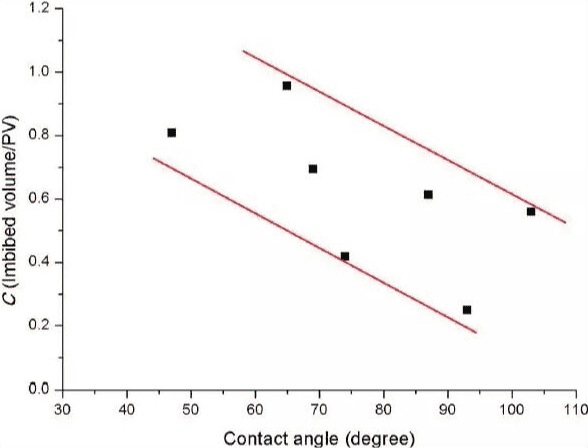

Contact angle measurements reveal the hydrophilicity of different coal samples. More hydrophilic samples allow water to spread more easily across surfaces and interiors, displacing non-wetting fluids. Coal wettability is influenced by composition, fluid properties, test environment, and pressure. Figure 6 shows that low-rank coals imbibe water faster than high-rank coals, consistent with wettability tests . Analysis of C-value versus contact angle confirms that smaller angles (higher hydrophilicity) correspond to higher C-values.

Figure 6: Relationship between Imbibition Capacity (C) and Contact Angle

04. Impact of Imbibition on Gas-Phase Permeability

Figure 7 shows a positive correlation between permeability damage index and contact angle. The four leftmost data points represent low-rank coals with contact angles <70°, high hydrophilicity, good pore connectivity, and higher C-values. Despite greater imbibition, low-rank coals suffer less permeability reduction than high-rank coals.

Figure 7: Relationship between Permeability Damage and Contact Angle due to Imbibition

Why does low-rank coal exhibit higher imbibition but lower permeability damage?

Analysis suggests that low-rank coals have permeability nearly two orders of magnitude higher than high-rank coals, meaning water invasion in high-rank coals more easily causes water-blocking and Jamin effects. About 90% of permeability loss occurs at ~45% water saturation in high-rank coals. In low-rank coals, the larger pore space allows water to enter along pore walls under capillary forces while gas continues to flow through the pore centre, so water does not fully block the pores, reducing water-blocking and Jamin effects, thus retaining some permeability.

5. Implications for Reservoir Development:

The interaction between fluids and coal during spontaneous imbibition varies by reservoir type, providing guidance for hydraulic fracturing and production strategy selection. For low-rank coal reservoirs, strong hydrophilicity drives significant fluid imbibition; reducing wettability via wettability alteration can decrease fluid imbibition. For high-rank coal reservoirs, lower inherent permeability is the main production constraint, so minimizing reservoir damage is crucial for maximizing gas output.

Yuan X, Yao Y, Liu D, et al. Spontaneous imbibition in coal: Experimental and model analysis[J]. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 2019, 67, 108-121.

Phone: 400-060-3233

After-sales: 400-060-3233

Back to Top